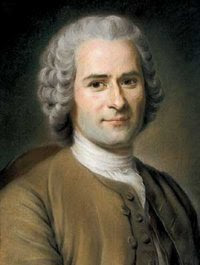

"Pour découvrir les meilleures règles de société qui conviennent aux nations, il faudrait une intelligence supérieure, qui vît toutes les passions des hommes et qui n'en éprouvât aucune, qui n'eût aucun rapport avec notre nature et qui la connût à fond, dont le bonheur fût indépendant de nous et qui pourtant voulût bien s'occuper du nôtre; enfin qui, dans le progrès des temps se ménageant une gloire éloignée, pût travailler dans un siècle et jouir dans un autre. Il faudrait des dieux pour donner des lois aux hommes."

(Discovering the rules of society best suited to nations would require a superior intelligence that beheld all the passions of men without feeling any of them; who had no affinity with our nature, yet knew it through and through; whose happiness was independent of us, yet who nevertheless was willing to concern itself with ours; finally, who, in the passage of time, procures for himself a distant glory, being able to labor in one age and find enjoyment in another. Gods would be needed to give men laws.) (Rousseau, Du Contrat Social)

I've thought a bit about this idea lately. Not exactly in the same context as Rousseau but in regard to how actually feeling something changes the way we look at something. I can expound philosophical truths about ideals all day long--and I hope that I would have the strength to stick with them--but somehow actually experiencing and feeling the real thing makes it clear just how hard it is to apply theory to reality. Rousseau says here that because man is not detached from emotion and passions, it is difficult to create a leader or society that is perfect.

This is my blog for the year I'll be spending in Germany doing research. I'll be poring over thousands and thousands of documents searching for an answer to why I decided to do a PhD. You can follow my musings and adventures here.

Monday, March 24, 2008

Saturday, March 22, 2008

Conservative Circles

.jpg)

"In any animal I see nothing but an ingenious machine to which nature has given senses in order for it to renew its strength and to protect itself, to a certain point, from all that tends to destrou or disturb it. I am aware of precisely the same things in the human machine, with the difference that nature alone does everything in the operations of an animal, whereas man contributes, as a free agent, to his own operations. The former chooses or rejects by instinct and the latter by an act of freedom. Hence an animal cannot deviate from the rule that is prescribed to it, even when it would be advantageous to do so, while man deviates from it, often to his own detriment. Thus a pigeon would die of hunger near a bowl filled with choice meats, and so would a cat perched atop a pile of fruit or grain, even though both could nourish themselves quite well with the food they disdain, if they were of a mind to try some. And thus dissolute men abandon themselves to excesses which cause them fever and death, because the mind perverts the senses and because the will still speaks when nature is silent." (Rousseau, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality)

I thought this passage was extremely interesting. I see it as a common practice to extract examples from nature to prove a political/ideological point. Rousseau here is railing against the tendency of man to abandon his natural boundaries and thus become degenerate. Others might point to natural patterns of reproduction, assembly, government etc. to prove their point. To me, it is not always clear if one can use such comparisons as the basis of truth. I guess the question is to what extent are the patterns we find in nature supposed to serve as a model for what is right. There are surely many examples of things that happen in nature that we would reject as being moral.

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

Impressions

"Impressions always actuate the soul, and that in the highest degree; but it is not every idea which has the same effect. Nature has proceeded with caution in this case, and seems to have carefully avoided the inconveniences of two extremes. Did impression alone influence the will, we should every moment of our lives be subject to the greatest calamities; because, though we foresaw their approach, we should not be provided by nature with any principle of action, which might impel us to avoid them. On the other hand, did every idea influence our actions, our condition would not be much mended. For such is the unsteadiness and activity of thought, that the images of everything, especially of good s and evils, are always wandering in the mind; and were it moved by every idle conception of this kind, it would never enjoy a moment's peace and tranquility... Nature has therefore chosen a medium, and has neither bestowed on every idea of good and evil the power of actuating the will, nor yet has entirely excluded them from this influence. Thought and idle fiction has no efficacy, yet we find by experience that the ideas of those objects which we believe either are or will be existent produce in a lesser degree the same effect with those impressions, which are immediately present to the senses and perception. The effect, then, or belief is to raise up a simple idea to an equality with our impressions, and bestow on it a like influence on the passions."(DAVID HUME from Treatise of Human Nature)

This has always been very interesting to me. I noticed that thoughts, while having the possibility to be powerful by themselves, are greatly accentuated when accompanied by a physical impression. I remember experiencing certain things as a missionary that I had read about a thousand times that made sense but made no great impression on me, but when the experience took place, it was as if thunder struck. The thought became a brand on my mind and heart when coupled with experience. I know that Hume is saying a lot more here, but this is just what I think of first when reading this.

This has always been very interesting to me. I noticed that thoughts, while having the possibility to be powerful by themselves, are greatly accentuated when accompanied by a physical impression. I remember experiencing certain things as a missionary that I had read about a thousand times that made sense but made no great impression on me, but when the experience took place, it was as if thunder struck. The thought became a brand on my mind and heart when coupled with experience. I know that Hume is saying a lot more here, but this is just what I think of first when reading this.

Thursday, March 13, 2008

People Movers

The way we humans try to legitimize things we do through categorization and names has always intrigued me. For example, there is this neighborhood by my house which has a big stone sign saying that the neighborhood is called "Venetian Villas" or something to that effect. Looking past the fact that the neighborhood is actually located in the Western U.S.--Orem, Utah to be exact--one can ask why we would feel this impulse to "borrow" the Venetian heritage.

What was my surprise then, when, traveling for the first time to the great state of Alaska, I meet this phenomenon, but going in the opposite direction. I had just hopped off my flight from Seattle to Anchorage with my traveling companion Andrew Christensen, and, having a few hours before our flight to Fairbanks, we decided that we wanted to see downtown Anchorage. We approached a friendly-looking police officer directing traffic and asked him if he knew where the buses to downtown Anchorage were. He looked at us kind of puzzled for a second and replied, "Oh, you mean the people mover. It is right over there." After recovering from this perplexing response, we proceeded to the before-mentioned location and we awaited the "people mover." Unfortunately we did not get to utilize the "people mover" due to time constraints, but we did consider taking a "personal people mover" (taxi), but eventually we decided on staying at the airport and eating before getting on the "flying people mover" to Fairbanks.

So basically I didn't realize that the great post-modernist movement has found a state that is committed to applying its principles in everyday life. We surely can't avoid categorizing, but we can simplify and render harmless our classifications as the Alaskans are finding out with their "people movers" (unless you are an Alaskan caribou who is left out of the picture with 'people' being in the title).

Saturday, March 8, 2008

Addendum to Camus' La Peste

Concerning Jesuit missionary activities among the Indians of North America and their medical practices there:

"The Jesuits of New France knew nothing of germs, viruses, and immunity. Though knowledgeable by the standards of their day, they lived centuries before modern science systematically classified diseases, discovered how they spread, and developed preventive and curative drugs. they brought to New France various medicines, including sugar,, widely regarded as a cure-all in the seventeenth century, and they were eager to learn about native herbal remedies as well. They also had recourse to the surgeon's art in serious cases, bleeding their colleagues or prescribing purges, treatments based on the prevalent theory that illness resulted form an excess of fluids in the body. The Jesuits did not see themselves as doctors, however. Their priority was saving souls, and when epidemics struck, they put most of their efforts into baptizing the dying rather than relieving the suffering of the living--a strategy that did not make a favorable impression on their native hosts.

As the Jesuits struggled to explain to their readers, and to themselves, the terrible epidemics that devastated the nations of North America, they tended to focus more on the ultimate question of why, rather than on the immediate question of how, disease spread. Seeing individuals and whole nations struck low, they perceived signs of God's plan to punish the wicked, test the resolution of the virtuous or simply gather souls to heaven. Since God worked through nature, explanations could be found in both religion and science, just as relief could be sought through prayer and medicine." (Greer, Allen, "The Jesuit Relations")

I see this as a continuation of the struggle between the ideal and the materialistic view of human nature. Camus says that before one can philosophize on theological causes for the problems in the world, one has to do everything one can to alleviate those problems. Pretty similar to Voltaire's Candide. I have personally been obsessed with the championing of the ideal, the power of the mind over matter, and in decrying pragmatism, but I am slowly gaining a more nuanced approach to this. I guess that is what comes with experience. I don't want to lose idealism though!

Sorting things Out

The Chinese Encyclopedia's Categories of Dogs, by Borges:

(a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies."

“We order the world according to categories that we take for granted simply because they are given.”

“An enemy defined as less than human may be annihilated.”

”All social action flows through boundaries determined by classification schemes, whether or not they are elaborated as explicitly as library catalogues, organization charts, and university departments.” (Darnton, French Cultural Tales)

These thoughts come from a book that seeks to explain the mindsets of 18th century frenchman with people of today. The point is made that a big portion of the way we make sense of the world comes from the way we classify things. To be honest, I think this is a lot deeper than I am able to grasp right now. All I can really think of now is the danger of letting established ways of classifying things determine how we see and interact with the world. It limits what we might consider proper and those things we might engage ourselves in otherwise. For example, cultural norms in worship services or how we approach learning in different disciplines; "this belongs to mathematics, this belongs to literature, and this belongs to history," whereas learning is one.

(a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies."

“We order the world according to categories that we take for granted simply because they are given.”

“An enemy defined as less than human may be annihilated.”

”All social action flows through boundaries determined by classification schemes, whether or not they are elaborated as explicitly as library catalogues, organization charts, and university departments.” (Darnton, French Cultural Tales)

These thoughts come from a book that seeks to explain the mindsets of 18th century frenchman with people of today. The point is made that a big portion of the way we make sense of the world comes from the way we classify things. To be honest, I think this is a lot deeper than I am able to grasp right now. All I can really think of now is the danger of letting established ways of classifying things determine how we see and interact with the world. It limits what we might consider proper and those things we might engage ourselves in otherwise. For example, cultural norms in worship services or how we approach learning in different disciplines; "this belongs to mathematics, this belongs to literature, and this belongs to history," whereas learning is one.

Thursday, March 6, 2008

Emotional Honesty

From an article entitled Emotional Honesty. Concerning our penchant for hiding our true emotions:

"...in many ways, society teaches us to ignore, repress, deny and lie about our feelings. For example, when asked how we feel, most of us will reply "fine" or "good," even if that is not true. Often, people will also say that they are not angry or not defensive, when it is obvious that they are.

Children start out emotionally honest. They express their true feelings freely and spontaneously. But the training to be emotionally dishonest begins at an early age. Parents and teachers frequently encourage or even demand that children speak or act in ways which are inconsistent with the child's true feelings. The child is told to smile when actually she is sad. She is told to apologize when she feels no regret. She is told to say "thank you," when she feels no appreciation. She is told to "stop complaining" when she feels mistreated. She may be told to kiss people good night when she would never do so voluntarily. She may be told it is "rude" and "selfish" to protest being forced to act in ways which go against her feelings.

Also, children are told they can't use certain words to express themselves. I have seen more than one parent tell their child not to use the word "hate," for example. And of course, the use of profanity to express one's feelings is often punished, sometimes harshly. In some cases the parent never allows the children to explain why they feel so strongly....At the same time, I have no doubt that part of a highly developed EI is knowing when to be emotionally honest, when to remain silent and when to act in line with or counter to our true feelings. There is something of a continuum of emotional honesty which includes unintended repression, full disclosure, discretionary disclosure, and intentional manipulation and emotional fraud. Furthermore, there is a constant trade-off between our short term vs. long term interests, our needs vs. others' needs and our self-judgement vs. judgement by others. Because all of this is largely an emotional problem to be solved, and a complex one at that, I believe emotional intelligence is being used when we make our decisions about when and how much to be emotionally honest. In my experience, approaching full emotional honesty simplifies my life, helps me see who will accept me as I am -- which in itself is a freeing discovery -- and offers me the opportunity for a rare sense of integrity, closeness and fulfillment.

Nathaniel Branden writes:

"If communication is to be successful, if love is to be successful, if relationships are to be successful, we must give up the absurd notion that there is something "heroic" or "strong" about lying, about faking what we feel, about misrepresenting, by commission or omission, the reality of our experience or the truth of our being. We must learn that if heroism and strength mean anything, it is the willingness to face reality, to face truth, to respect facts, to accept that that which is, is."

This is now me speaking. As usual, I don't think I have any absolute answers. I am starting to doubt that things are that simple. These blog posts are mostly equivalent to indulging in thoughts, and since I am usually against most types of indulgences, this may be out of character. In any case, I have trouble with this concept of emotional honesty. Naturally I am too open with my feelings. I may end up telling a complete stranger how I am really feeling. I just assume that when someone casually says "how's it going?" that they actually mean it as a question and not just a greeting.

Despite this side to my nature, many things over the years have told me to suppress expressing my feelings freely. As a missionary I was convinced that I should basically let anything that bothered me just be ignored. It was my problem if I got annoyed or upset. I still am very persuaded by a talk from conference where a seventy talked about a wife that decided a good exercise would be to share five things that were bothering them each concerning their partner. She went first talking about small things like how he ate his food, etc. When it was his turn, he just said that he couldn't think of anything about her that bothered him. The talk's moral was to let little things like that slide. While I still think that this should often be the case, I am wondering if it isn't better to take the advice of this article and be more open. I agree that trust is probably best built in an atmosphere where one shares more than one conceals, but at the same time, how do create this atmosphere that encourages openness? Furthermore, this article says that "emotional intelligence" consists of being able to tell when one should be emotionally honest. She doesn't say more though. And neither do I.

"...in many ways, society teaches us to ignore, repress, deny and lie about our feelings. For example, when asked how we feel, most of us will reply "fine" or "good," even if that is not true. Often, people will also say that they are not angry or not defensive, when it is obvious that they are.

Children start out emotionally honest. They express their true feelings freely and spontaneously. But the training to be emotionally dishonest begins at an early age. Parents and teachers frequently encourage or even demand that children speak or act in ways which are inconsistent with the child's true feelings. The child is told to smile when actually she is sad. She is told to apologize when she feels no regret. She is told to say "thank you," when she feels no appreciation. She is told to "stop complaining" when she feels mistreated. She may be told to kiss people good night when she would never do so voluntarily. She may be told it is "rude" and "selfish" to protest being forced to act in ways which go against her feelings.

Also, children are told they can't use certain words to express themselves. I have seen more than one parent tell their child not to use the word "hate," for example. And of course, the use of profanity to express one's feelings is often punished, sometimes harshly. In some cases the parent never allows the children to explain why they feel so strongly....At the same time, I have no doubt that part of a highly developed EI is knowing when to be emotionally honest, when to remain silent and when to act in line with or counter to our true feelings. There is something of a continuum of emotional honesty which includes unintended repression, full disclosure, discretionary disclosure, and intentional manipulation and emotional fraud. Furthermore, there is a constant trade-off between our short term vs. long term interests, our needs vs. others' needs and our self-judgement vs. judgement by others. Because all of this is largely an emotional problem to be solved, and a complex one at that, I believe emotional intelligence is being used when we make our decisions about when and how much to be emotionally honest. In my experience, approaching full emotional honesty simplifies my life, helps me see who will accept me as I am -- which in itself is a freeing discovery -- and offers me the opportunity for a rare sense of integrity, closeness and fulfillment.

Nathaniel Branden writes:

"If communication is to be successful, if love is to be successful, if relationships are to be successful, we must give up the absurd notion that there is something "heroic" or "strong" about lying, about faking what we feel, about misrepresenting, by commission or omission, the reality of our experience or the truth of our being. We must learn that if heroism and strength mean anything, it is the willingness to face reality, to face truth, to respect facts, to accept that that which is, is."

This is now me speaking. As usual, I don't think I have any absolute answers. I am starting to doubt that things are that simple. These blog posts are mostly equivalent to indulging in thoughts, and since I am usually against most types of indulgences, this may be out of character. In any case, I have trouble with this concept of emotional honesty. Naturally I am too open with my feelings. I may end up telling a complete stranger how I am really feeling. I just assume that when someone casually says "how's it going?" that they actually mean it as a question and not just a greeting.

Despite this side to my nature, many things over the years have told me to suppress expressing my feelings freely. As a missionary I was convinced that I should basically let anything that bothered me just be ignored. It was my problem if I got annoyed or upset. I still am very persuaded by a talk from conference where a seventy talked about a wife that decided a good exercise would be to share five things that were bothering them each concerning their partner. She went first talking about small things like how he ate his food, etc. When it was his turn, he just said that he couldn't think of anything about her that bothered him. The talk's moral was to let little things like that slide. While I still think that this should often be the case, I am wondering if it isn't better to take the advice of this article and be more open. I agree that trust is probably best built in an atmosphere where one shares more than one conceals, but at the same time, how do create this atmosphere that encourages openness? Furthermore, this article says that "emotional intelligence" consists of being able to tell when one should be emotionally honest. She doesn't say more though. And neither do I.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)